NAOSHIMA AND TESHIMA, Japan — It takes a taxi, five train changes, and a ferry. Only in Japan, where things run like clockwork, could this journey take less than a day. We have traveled 400 miles — about the distance from Boston to Washington, D.C. — from the town of Izunokuni, near Mt. Fujiyama, to Naoshima, one of a cluster of islands in the Seto Inland Sea.

Naoshima is one of three “art islands” in the Seto Sea (the other two are Teshima and Inujima), housing contemporary art in museums and outdoors. We are spending one night on Naoshima and two on Teshima, where quirky art and breathtaking scenery greet the few visitors who venture there.

Until the 1990s, these were rural islands with dwindling populations because young people born here moved to the cities. Then everything changed when Japan-based Benesse Holdings, which owns Berlitz Language Schools, led the rejuvenation. The company houses its growing art collection here. Today Naoshima is mecca for art lovers, who can see works inside a modern museum and other buildings, and grand sculptures scattered over the islands.

From the ferry to Naoshima, we spot a 13-foot-tall, hollow red pumpkin on the pier, a creation of pumpkin-obsessed artist Yayoi Kusama. Our children, 10 and 12, run into the pumpkin to peep through the holes on its surface. A few hundred yards away is Japanese architect Sou Fujimoto’s “Naoshima Pavilion,” a geometric structure made from a net of 250 steel rods. The children, pretending they are trapped inside, have to be coaxed onto the bus to the hotel.

We drive south to Benesse House Museum, where we are staying in one of the six rooms at the “Oval,” atop a hill reachable only by monorail from the museum. Floor-to-ceiling windows in our room offer a stunning, panoramic view of the ocean. We are headed to the museum for a 10-course kaiseki, a traditional multicourse meal.

The next morning, taking the monorail down, we notice art installations on a secluded part of the beach, past a wooded area, The island’s brochure calls them “Shipyard Works,” by renowned artist Shinro Ohtake. One, aptly named “Stern With a Hole,” is shaped like a ship’s stern and looks like a mesh with its numerous holes. The other, “Cut Bow,” is embedded in the sand like a giant sea shell.

Further up the slope, against a clear blue sky is “Three Squares Vertical Diagonal” — large metal squares perched on their corners. The late American kinetic sculptor George Rickey created these; the squares move with the slightest air disturbance, so observers can experience time’s flow.

The day is perfect for exploring this 5½-square-mile island — crisp air and not a cloud in the sky. Armed with the map we walk to the “Park Area,” where self-taught Japanese architect Tadao Ando has designed a wooden building where tourists can stay. Scattered in the lawn in front are colorful artworks with animal and human motifs and a little further, another Kusama pumpkin. This one is yellow, at the end of the concrete jetty; the mountain ranges on neighboring Shikoku tower on the far shore.

After the walking tour, we pack up to catch the ferry to Teshima, and pass “Drink a Cup of Tea,” a Japanese-style blue metal cup perched on a stone platform. Artist Kazuo Katase drew inspiration for this work after watching a Buddhist Zen ritual with teacups to evoke truth-seeking spirits.

Close to the museum is “Seen/Unseen Known/Unknown,” by the late American artist Walter de Maria, who used light for creating intense psychic experiences. Two granite balls and gold bars are housed within a concrete structure creating different shadows as you move, emphasizing the existence of light. The bars disappear when you stand between the spheres and when you move a little, one sphere disappears.

The ferry to Teshima is only 20 minutes, which makes us wonder if we shouldn’t have spent another night on Naoshima and done a Teshima day trip. But we have made the right decision. We fall in love with the 5.6-square-mile Teshima island with its terraced rice fields tucked in forested mountains. Less than 1,000 people live here in three fishing villages — Ieuraoka, Karato, and Kou.

There are few tourists and accommodations are limited. We had booked a newly-opened Airbnb in Ieuraoka for two nights and the owner, Keiko Tada, was waiting at the ferry to drive us to the house. Tada, an Emerson College graduate, gives us tips on how to navigate the island. She takes us to a renovated traditional Japanese house on a quiet street.

We explore Ieuraoka in the calm afternoon silence. Our first stop is “Needle Factory,” a closed sewing needle factory housing a 17-meter hull that lay neglected for 30 years until Ohtake, the artist whose work we had seen on Naoshima, rescued and installed it in the factory. Ohtake combined two abandoned entities, each carrying its own memories, in a common space.

The only way to get around Teshima is by foot, on rental bicycles, or on a madly-decorated “Beautiful Island Bus,” that circles the island all day long. We take the bus to Karato, where most of the art is housed; the ride is several miles on steep, windy mountain roads.

The bus drops us off by the ocean, east of Karato, near “Les Archives du Coeur,” a squat building that houses heartbeats of people around the world. In the “Heart Room,” lights get brighter and dimmer in sync with recorded heartbeats. You can record your own in another room or listen to the heartbeats of others in a third room. It is at once unique and morbid and I am happy stepping out to enjoy the view of the ocean.

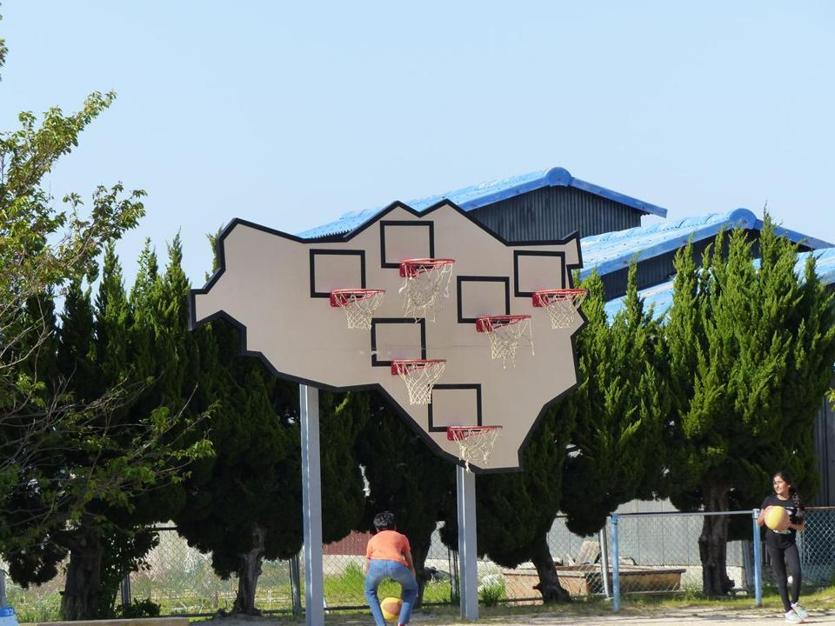

The sun is going down and we hop on a bus back to our house. Near the bus stop we see six basketball hoops mounted on a board: another installation, called “No One Wins — Multibasket.” The children grab a basketball each and begin throwing them through the hoops. Soon, other tourists join in and the purpose of the art is revealed — the human ability to enjoy something with strangers.

Early the next day we explore the charming village of Karato with its windy streets and quaint houses. Around a corner is a breathtaking view of rice fields disappearing into the blue ocean. Opposite is a Shinto shrine with a water tank over which are several circular iron hoops. Yes, another art installation, “Particles in the Air,” where the hoops represent dancing air particles.

Teshima’s tallest mountain, Dan Yama, rises from the island’s center and houses “La Foret de Murmures,” or the “Whispering Forest.” To get there, we walk halfway up the 1,100-foot mountain on a dirt path. In the forest 400 wind chimes tinkle, creating a different melody every second. Strips of transparent paper on the chimes have names of the loved ones of visitors.

On the way down we stop at a small eatery hidden behind a tree thicket. At Shokudoi 101, lunch is satisfying: bowls of hot miso soup, rice, steamed vegetables, and tofu seasoned with togarashi, a Japanese spice blend. We grab dessert at “Lemon Hotel,” an art installation doubling as a hotel (only one double room; reservations have to be made well in advance). The hotel is a traditional Japanese home surrounded by fragrant lemon groves. A veranda of lemon-scented silk sheets billow in the breeze. You can wrap yourself in the sheets and the fragrance is divine.

We walk through a bath area with a tub filled with lemon-scented water, into a hallway with a lemon-yellow phone, and end up in a tatami room with fabric dyed in lemon. At the hotel restaurant, the menu is all lemon scented — scones, lemonade, and lemon beer.

Our last stop is the Teshima Art Museum, a simple, white concrete shell tucked in verdant rice fields. The shape represents a water drop and two large openings in the semicircular ceiling let in all the elements. We sit on the concrete floor, through which water drops spring out. It is calming watching a drop emerge from the ground and follow a path determined by how the elements are interacting at that moment. Signs ask for complete silence but they are unnecessary — the place inspires quiet and even the children sit still for half an hour. It is the end of our trip to these islands and before we return to the real world, we have a moment to think about the grandeur here.